|

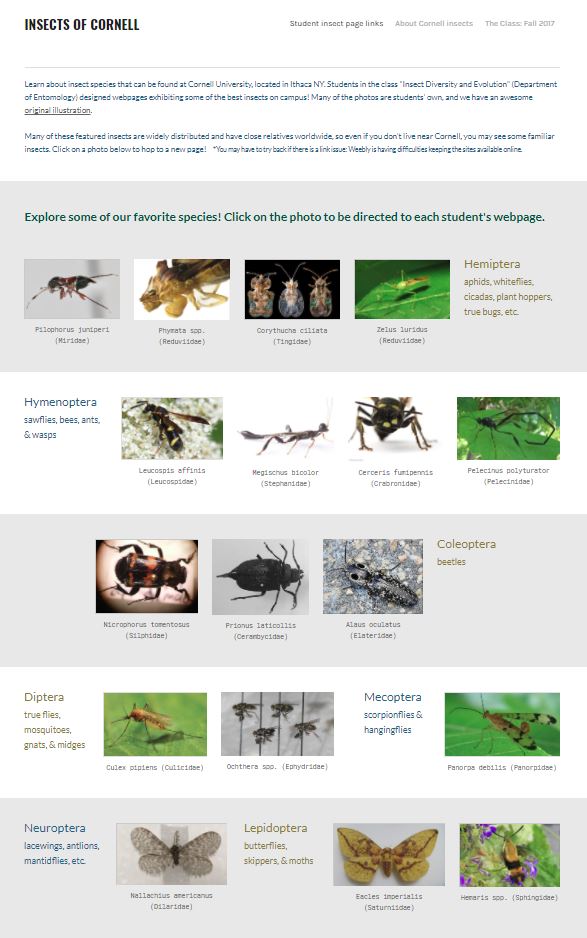

For the course I'm teaching this fall (Insect Diversity and Evolution, ENTOM 3310/3311), the students each designed a webpage on their favorite species of insect that could be found at Cornell. Check it out!

We used the free Weebly for Education platform. None of the students had made their own website prior to this semester & overall, it seemed like the students caught on quickly. The biggest problem I encountered is that the individual sites are often down. Clicking on the link gives a message: "This page isn't working" -- which is an issue on the Weebly end. That's a little disappointing, and I hope it improves.

5 Comments

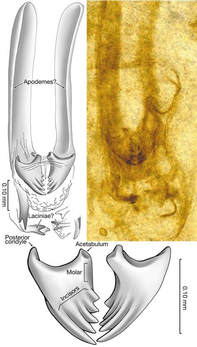

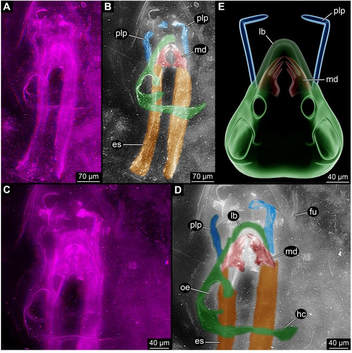

The fossil that was thought to be the oldest flying insect (and has been used to interpret and date the origins of flight) may not even be an insect at all! In an interesting turn, a recent publication asserts that the fossil Rhyniognatha hirsti is not the mandible of a flying insect, but is in fact a fragment of a myriapod: specifically, an immature centipede. In an article published May 30, 2017 in the journal PeerJ, Haug & Haug present evidence that the Devonian fossil R. hirsti (>400 My old) is not a flying insect... or an insect... or even closely related to insects... It is a centipede. The fossil is fragmentary, mainly mandibles and some other rather ambiguous parts connected to it. However, the shape of these mandibles was similar to those of dragonflies and neopterans, which prompted Engel and Grimaldi (2004) to tentatively assign it as a fragment of a flying insect. Now, Haug & Haug use 3D imaging and show remains of what they hypothesize is a myriapod-like head capsule. Also, the putative apodemes are deemed to be glands of ectodermal origin. The potential misplacement of this fossil has some pretty big implications. The next oldest fossils of flying insects are from the late Carboniferous -- about 80 My after this fossil! That is a huge time difference and affects our interpretation of the origins and evolution of insect flight. Also, many molecular phylogenetic studies have used this as a fossil calibration. For instance, the hexapod dated phylogeny of Misof et al. 2014 incorporated this fossil as a stem calibration for Dicondylia (winged insects + their sister group Diplura), with an age of 411.5 Mya. The reinterpretation of this fossil, if it is accepted, will have wide effects on future work on insect evolution and dating. As of September 23, there were ~1500 views of the article and no papers citing it, so we'll have to stay tuned for a response! references:

Engel, M.S. & Grimaldi, D. (2004) New light shed on the oldest insect. Nature 427, 627-630. Haug, C. & Haug, J.T. (2017) The presumed oldest flying insect: more likely a myriapod? PeerJ, 5, e3402. Misof, B., Liu, S., et al. (2014) Phylogenomics resolves the timing and pattern of insect evolution. Science, 346, 763-767. Have you heard of 'The Amphioxus Song'? The song is an ode to the lowly lancelet (another name for this organism). Amphioxi are heralded due to their similarity to early chordates, exhibiting characters showing evolutionary development to the vertebrates.

A Nature blog from 2008 highlights the Amphioxus song and also gives links for a series of posts on "Songs About Science", some of which are at least somewhat entertaining. As far as science songs go, I'd also recommend the Cane Toad Blues from the documentary 'Cane Toads: An Unnatural History'.

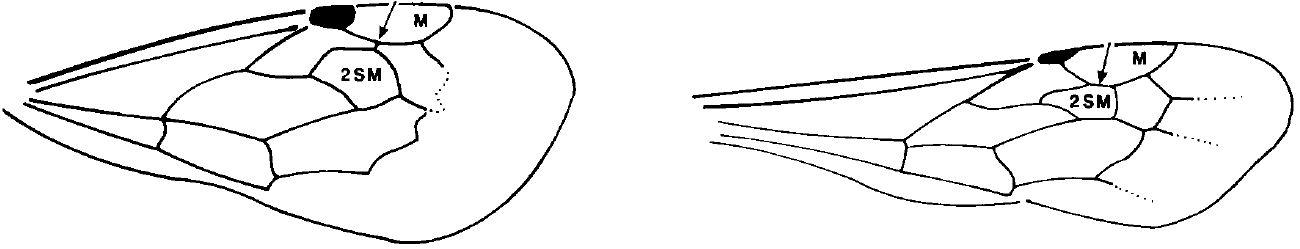

A taxonomic key couplet distinguishes between a sessile wing cell and a petiolate wing cell -- but what does that mean? Look at the crossveins, not the shape of the cell itself. Wing venation is a critical component of many insect keys. (I was accustomed to the reduced venation of Chalcidoidea but am now in a bee lab, dealing with larger and more venous hymenopterans.) An anteriorly sessile versus anteriorly petiolate 2nd submarginal cell (2SM or SM2) is a character that is important in some sphecidoid and vespidoid groups. While working through keys and double-checking terminology, it was hard to find online guidance on the sessile/petiolate distinction. I finally got smart and consulted the book 'Hymenoptera of the World' (Goulet & Huber 1993). The wing on the left shows 2SM petiolate anteriorly, because it does not touch the marginal cell (M), but is connected to it by a crossvein (like a petiole). The wing on the right is an example of 2SM sessile anteriorly, because 2SM touches M, sharing a common vein. Image from Hymenoptera of the World. reference: Goulet, H. & Huber, J.T. (1993) Hymenoptera of the world: An identification guide to families. Agriculture Canada, Ottawa, Canada. [page 190, mutillid key]

|

PhyloBlogCovering topics of phylogenetics and systematics & other science-related news. Archives

October 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed