|

And. But. Therefore. These three words give a clear format for telling a narrative, writing a scientific abstract, or organizing a conference talk. After reading "Houston, We Have a Narrative", I have been incorporating this structure into my scientific work. Have you tried out 'ABT'?

Some scientists may shy away from visualizing their research as a story to be told, but Olson argues that a narrative is what humans are built to respond to. He defines a narrative (p 182) as "a series of events that happen along the way in the search for a solution to a problem". A narrative is not a fictional piece of work, and it doesn't have to be non-scientific. I'd recommend checking out the book! If you attended the Entomological Society of America meeting in Vancouver (Nov. 2018), maybe you saw Randy Olson's plenary talk. He explained a newer concept he developed called the 'Narrative Index' where he calculates the ratio of BUTS to ANDS (x100) in speeches or writings. Higher is better & shows a stronger narrative. For instance, he calculated the Lincoln-Douglas debates (Lincoln was better with a mean score of 20, instead of Douglas's score of 9.29). At the bottom of his web page, you can see what Olson has calculated for other presidents, and what he finds as Donald Trump's scores. reference: Olson, R. (2015) Houston, we have a narrative: Why science needs story. University of Chicago Press.

0 Comments

Did you know that bees evolved from within a group of solitary, carnivorous wasps, approximately 120 million years ago? Today, pollinivory – the consumption of pollen – is a defining feature of bees (aptly named Anthophila; the flower lovers).

In this study, one of the core concepts is the role of the ‘key innovations’ underlying biodiversity patterns. A key innovation is an evolutionary novelty which is believed to contribute to the success of a group. (For example, across all insects, some of the major transitions that are hypothesized to be key innovations include the origin of wings/flight, and the origin of complete metamorphosis.) Under the traditional definition of innovation, we would predict that a lineage with the key trait is more speciose than related groups lacking this key trait. The switch to pollen feeding has been assumed to be a key innovation of bees: the bees arose from within a group of carnivorous wasps, were able to exploit a new food resource, and today are extremely species rich. Our finding that not all bees exhibit a high diversification rate challenges conventional thought that the switch to pollinivory is directly responsible for increased bee diversity. We found that some of the earliest-originating bees did not partake in the diversification upswing. These results indicate that pollen feeding was an important evolutionary switch, but does not fully explain the diversity we see today. We postulate that other complementary innovations, such as a generalist host-plant diet, influenced the tremendous diversification of the major bee lineages. On a broader scale, this study contributes to an area of interest in the insect scientific community, of investigating whether diet shifts to plant-feeding contribute to higher diversity. Pollinivory is a specialized form of herbivory. Classic and contemporary studies have found a general pattern across insects that herbivory increases diversification (i.e., Mitter et al. 1988 & Wiens et al. 2015). We found that the evolutionary shift to plant-feeding contributed to bee diversification, but our results indicate it is not directly responsible for the increase in diversification rates. The Cornell Chronicle published an article on our paper! Read it here: Study Challenges Widely Held Assumption of Bee Evolution. citation: Murray, E.A. Bossert, S., Danforth, B.N. (2018) Pollinivory and the diversification dynamics of bees. Biology Letters, 14, 20180530. DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2018.0530

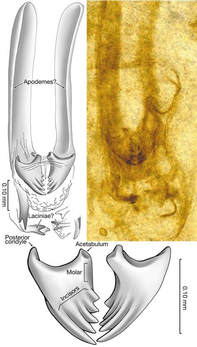

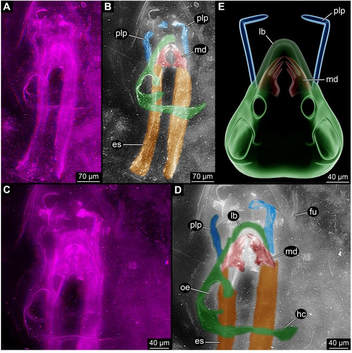

The fossil that was thought to be the oldest flying insect (and has been used to interpret and date the origins of flight) may not even be an insect at all! In an interesting turn, a recent publication asserts that the fossil Rhyniognatha hirsti is not the mandible of a flying insect, but is in fact a fragment of a myriapod: specifically, an immature centipede. In an article published May 30, 2017 in the journal PeerJ, Haug & Haug present evidence that the Devonian fossil R. hirsti (>400 My old) is not a flying insect... or an insect... or even closely related to insects... It is a centipede. The fossil is fragmentary, mainly mandibles and some other rather ambiguous parts connected to it. However, the shape of these mandibles was similar to those of dragonflies and neopterans, which prompted Engel and Grimaldi (2004) to tentatively assign it as a fragment of a flying insect. Now, Haug & Haug use 3D imaging and show remains of what they hypothesize is a myriapod-like head capsule. Also, the putative apodemes are deemed to be glands of ectodermal origin. The potential misplacement of this fossil has some pretty big implications. The next oldest fossils of flying insects are from the late Carboniferous -- about 80 My after this fossil! That is a huge time difference and affects our interpretation of the origins and evolution of insect flight. Also, many molecular phylogenetic studies have used this as a fossil calibration. For instance, the hexapod dated phylogeny of Misof et al. 2014 incorporated this fossil as a stem calibration for Dicondylia (winged insects + their sister group Diplura), with an age of 411.5 Mya. The reinterpretation of this fossil, if it is accepted, will have wide effects on future work on insect evolution and dating. As of September 23, there were ~1500 views of the article and no papers citing it, so we'll have to stay tuned for a response! references:

Engel, M.S. & Grimaldi, D. (2004) New light shed on the oldest insect. Nature 427, 627-630. Haug, C. & Haug, J.T. (2017) The presumed oldest flying insect: more likely a myriapod? PeerJ, 5, e3402. Misof, B., Liu, S., et al. (2014) Phylogenomics resolves the timing and pattern of insect evolution. Science, 346, 763-767. The EvoGroup at Cornell recently hosted the annual EvoDay conference, held at the Lab of Ornithology. This year's theme was 'Phylogenomics'.

Each year at EvoDay there is a mix of faculty, researchers, postdocs, and grad students who give ~20 minute presentations at the event, addressing an audience of about 100 people. Past themes have been 'Evolution and Conservation' (2016) and 'Evolution and Behavior' (2015).

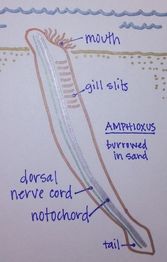

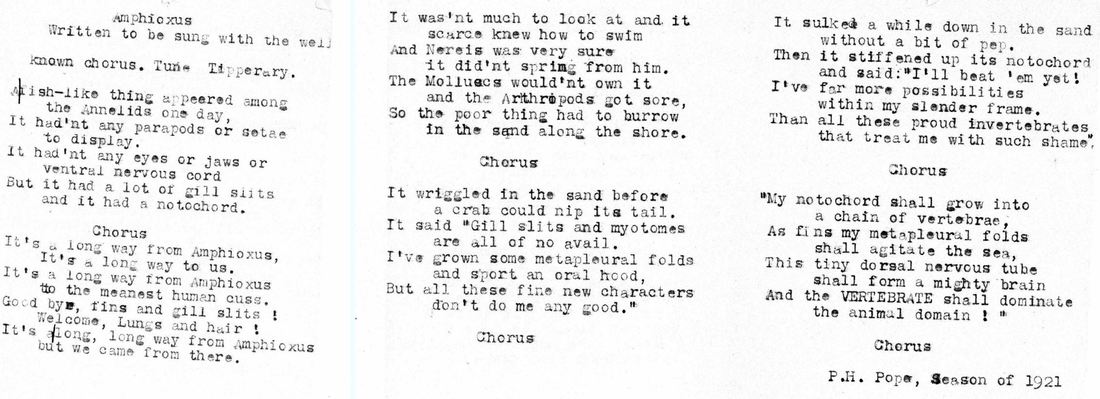

This year, our aculeate working group was well-represented, as both Bonnie Blaimer (Smithsonian) and I presented our latest work based on phylogenies constructed from ultraconserved elements (UCEs). Have you heard of 'The Amphioxus Song'? The song is an ode to the lowly lancelet (another name for this organism). Amphioxi are heralded due to their similarity to early chordates, exhibiting characters showing evolutionary development to the vertebrates.

A Nature blog from 2008 highlights the Amphioxus song and also gives links for a series of posts on "Songs About Science", some of which are at least somewhat entertaining. As far as science songs go, I'd also recommend the Cane Toad Blues from the documentary 'Cane Toads: An Unnatural History'.

|

PhyloBlogCovering topics of phylogenetics and systematics & other science-related news. Archives

October 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed